How the Catholic Church Saved New York City | Pt.1

Travel back in time and discover the untold stories of the Church in Old New York

Overcoming violent anti-Catholicism, poverty, and gangs, the Sisters of Charity opened the doors of opportunity to generations of immigrants.

The narrow hallways of 32 Prince Street in Lower Manhattan silently echo with the stories of an age gone by: the long-lost voices of orphan children clamoring in the small courtyard as the nuns would scurry about ushering them across the street for Sunday Mass at the just dedicated “Old” St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mott Street, a faded portrait of grace and beauty painted on a canvas that at the time could easily have been mistaken for hell.

The beginning

The year was 1815, and New York “City” would be completely unrecognizable to those who identify it by its soaring skyscrapers and broad avenues. It was a time when Canal “Street,” actually a canal at the time, was the northernmost boundary.

Beyond it were rolling hills, forests, and farms leading clear up the Hudson River. While the “teeming” population of 80,000 supported itself through traditional trades, New York was rapidly becoming the import/export capital of the country with its expansive port and sheltered harbor.

The fledgling Catholic community, made up mainly of Irish, German, and French immigrants, was the religious minority, and anti-Catholic sentiment among the descendants of colonists was de rigueur. Few churches, and even fewer priests, made access to the sacraments a challenge.

On November 24, 1815, following a grueling sea passage that had many convinced she had met her end in the depths of the Atlantic, the 147-ton brig ‘Sally’ dropped anchor in New York Harbor, depositing a weary 68-year-old Bishop John Connolly on the bustling docks of the East River.

Connolly, being the second bishop of New York, was the first to set foot on its cobbled streets, as the previous bishop lost his life in the Napoleonic Wars before he could ever make the journey to the New World.

Historian Monsignor Peter Guilday of Catholic University remarks, “It may well be doubted if, in the entire history of the Catholic Church in the United States, any other bishop began his episcopal life under such disheartening conditions.”

Some 15,000 Catholics, four priests, and three churches … one of which was 300 miles north, in Albany: This new flock, which was suffering abject poverty, disease, and anti-Catholic bigotry, welcomed their new shepherd with hope.

And he set about the business of serving his flock with enviable zeal, attracting vocations, opening parishes, and penning a letter that would ultimately lead to one of his most notable achievements.

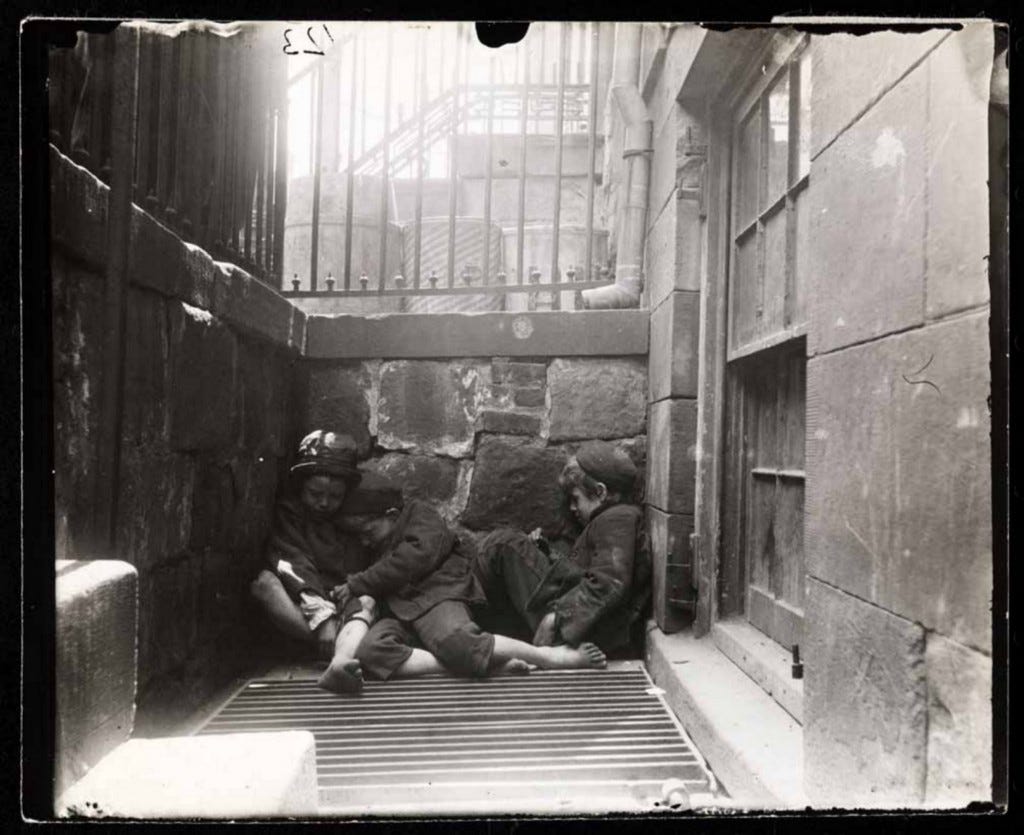

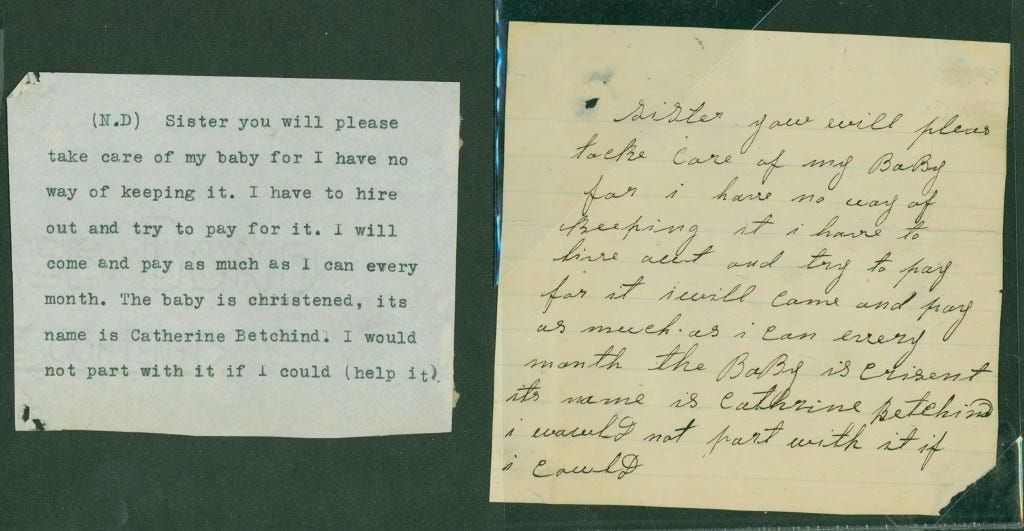

Among the imminent challenges facing the new bishop was that of homeless children. Prostitution and contracted life expectancy among adult parents due to disease led to an abundance of orphaned infants and children left to the streets.

So in a letter dated July 14, 1817, to Mother Elizabeth Ann Seton, whose growing order, the Sisters of Charity, had taken up residence in Emmitsburg, Maryland, Bishop Connolly implored her to send three nuns to open an orphanage to serve the dire needs of his burgeoning see.

And barely a month later, on August 20, 1817, Sr. Rose White, Sr. Cecilia O’Conway, and Sr. Felicite Brady of the Sisters of Charity arrived at their first home in New York, a small post-Revolutionary field hospital known as “The Dead House.”

Its wide plank floors were so stained with soldiers’ blood that no amount of scrubbing would ever remove the memory of those who crossed the threshold.

Within a week’s time, the Sisters welcomed the first five orphans into the shelter, and the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum of the Sisters of Charity, the first Catholic orphanage in the United States, was established. By cleverly arranging the interior space, they managed to accommodate 23 additional orphans, bringing the number to 28.

Over the next few years, the orphanage grew in size and population and was frequently visited by both benefactors and volunteers. Among them was a young black girl named Euphemia Toussaint and her uncle, Pierre, who would arrive bearing pastries and fruits to throw a great celebration for the young girls’ birthdays.

It is said that Euphemia’s heart was with the orphans from her early childhood, and after her tragic passing at only 14 years of age, her uncle, who had previously been instrumental in raising funds for both the church and orphanage, redoubled his efforts, even opening his own home at 105 Reade Street to shelter and educate orphans. Euphemia was laid to rest in view of the orphanage in the cemetery at St. Patrick’s on May 11, 1829.

From humble beginnings in a city not yet realized, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton’s prophetic decision to send the three pioneering nuns to what would become the greatest city in the world laid the foundation for over 180 schools, 28 hospitals, 23 childcare institutions, and countless other ministries providing Faith-guided care that allowed generations of impoverished immigrants to build lives filled with promise, and build the city of dreams.

Add to their litany of service, in 1862, their care for the wounded soldiers returning from the Civil War, which dramatically altered how Catholics were viewed at the time.

In 1912 they received and cared for the survivors of the ill-fated R.M.S. Titanic at St. Vincent’s Hospital, and in the 1950s, taught a young Martin Scorsese how to read and write at their St. Patrick’s School on Mott Street.

In the dramatic tale of New York City, the Sisters of Charity have played an epic role as Catholic women, caregivers, and educators, profoundly shaping the very soul of the city of concrete and steel.

The legacy of their heroic work is indivisibly woven in the rich cultural fabric of a city of men and women drawn by the promise of a better life … and a better life was exactly what the Sisters of Charity afforded them.

St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, please pray for us.

[Originally published on Aleteia.org]